In this short blog essay I will present my perspective on Modern Monetary Theory (further referred to as MMT) - a new clever macroeconomic theory and why I belive it to be equivalent to raising taxes.

What is MMT?

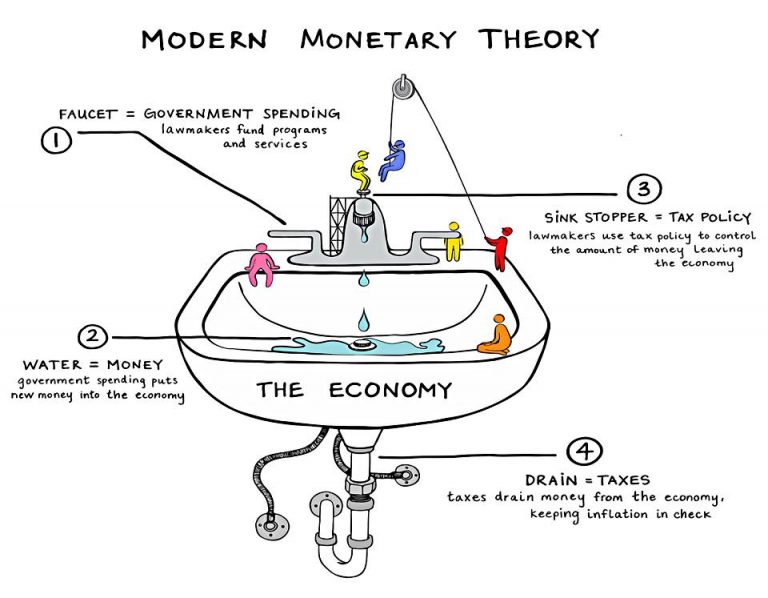

Modern Monetary Theory is a macroeconomic theory that asserts that countries with monetary sovereignity (countries with full control over their currency and whose currency is held and desired by other central banks and which does not hold large foreign currency debts) like the US, Canada, UK, Japan and China, but not the EU (as member states with fiscal sovereignity do not have monetary sovereignity) and not countries like Pakistan, Chile or Argentina (whose currencies are not generally sought after by other central banks and their own citizens), are not constrained by tax revenues when it comes to government spending.

MMT postulates that governments can spend more than they receive in taxes since they can simply issue more currency. The resulting inflation can be controlled up to a reasonable degree with increased taxation (additionally it ensures that people use the currency as they have to pay taxes in it). According to MMT the government doesn’t even need to issue bonds and can simply set a 0% interest rate, as inflation can be controlled with taxes.

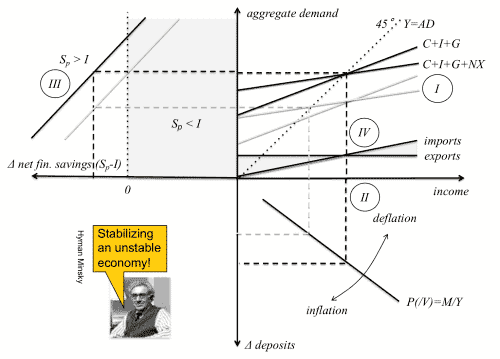

I really like the visualizations by Dirk Ehnts from Social Europe, which I’ll use here and the quote by John Maynard Keynes from 1942:

“Anything we can actually do we can afford. Once done, it is there.”

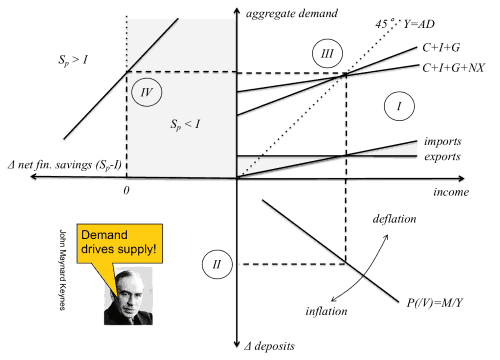

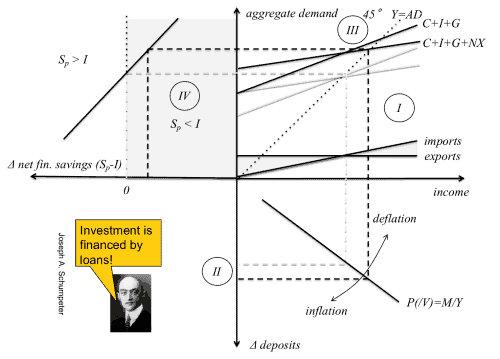

Let Sp be private savings (including repaying debt), I be the private investment. Then the aggregate demand (AD) - the total investment I, government spending G, consumption C and exports NX is proportional to the amount of financial assets being saved up (any Euro saved is an Euro not spent). These relationships are shown in the upper two quadrants. The lower right quadrant explains the relationship between the money supply (M - the amount of money), velocity of money exchange (V), average price level (P) and the real output of the economy (Y), giving the well known equation: M V = P Y

An increase in private investment (I) improves the employment and national income:

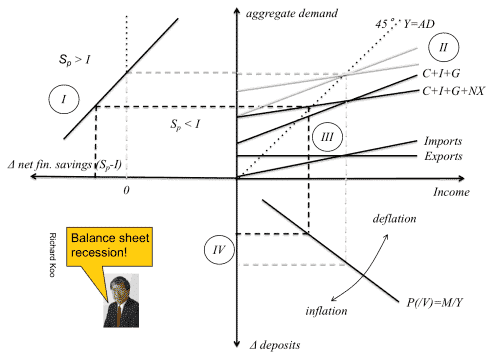

Likewise a decrease in private investment or a massive spike in private savings leads to a lower output:

And now we arrive at the Keynesian step; If private investment does not rise in spite of a 0% interest rate, then growth will not come from itself in the short-run and it makes sense to increase government spending to stimulate the economy. The classical quote that I really like by Keynes comes to mind:

“In the Long Run we are all dead” - John Maynard Keynes

However the difference of opinion between Keynesians and MMT is how that money is to be obtained:

- Keynesians advocate for taking out debt and repaying that debt during times of plenty. Taxes are not increased to maximise AD, but ideally even decreased.

- MMT advocates for issuing more currency to pay for the interest needed for the increase in spending. Taxes are increased only to control inflation, which results from an increase in AD and/or the money supply.

MMT is implicit taxation

In my view MMT works just like taxation; Resources in every economy at time t are finite and money is used to evaluate the value of these resources (based on microeconomic equilibria) - this evaluation of course depends on the total supply of money (and the circulation speed). Assuming the velocity of money exchange is somewhat constant in a tight time interval (Δt->0), the introduction of new currency (let’s say by 2%) by a government (and note that the amount of currency held by currency users stays constant) means that 2% of the economic value has been transfered to the government, or with other words the 2€ previously held by its users is now worth 1,96€, the other 0,04€ can be spent freely by the government. Since money is a social construct but resources are real, issuing currency is an invisible transfer of value to the government. Often government spending leads to investment (in critical infrastructure - something which the private sector typically does not provide due to the free rider problem) which increases the total number of resources, which can offset this inflationary impact, but only assuming the amount of the created currency is proportional to the the amount of resources created, which typically happens with a delay.

The classical approach would be to issue a 2% tax, that way the government can still spend and invest the collected money and the user can still only spend 1,96 € of his original 2,00 €, but the costs are explicit and do not cause inflation unlike with MMT, where the value transfer is hidden (you still have your 2,00€ even though it becomes de facto equivalent to 1,96€).

The biggest benefit of MMT is that it allows the government to de facto collect funds without taxing people - as taxation is inately unpopular. MMT offers a pain-free alternative.

The unexpected problems MMT solves

Asides from goals like ensuring full employment and providing everyone with the right to a job, MMT provides an unorthodox solution to some major problems.

One of the unexpected big problems that MMT solves with taxation are the issues of capital flight and partly the Laffer curve problem. One of the key problems governments face when raising taxes is the prospect of affluent people, investors and entrepreneurs moving to a country with lower taxes, and the Laffer curve - which states that increasing tax rates beyond a certain point can actually lead to a decrease in revenue because it disincentivizes work, investment, and economic activity, ultimately reducing the taxable base.

MMT offers an alternative, where taxes do not have to raised significantly in order to increase government spending, effectively bypassing the problems that come with taxation. A government increasing its spending with MMT still implicitly raises revenue from the value transfer when currency is issued, but since this is achieved with the currency, capital flight is effectively avoided and the Laffer curve isn’t a concern anymore.

A major hidden benefit of MMT is competitiveness on the global markets - especially as technological progress is accelerating, any slowdowns due to budget constraints can lead to a country falling behind in the technology sector and other countries may manipulate other markets as well, which means that one of the only ways of protecting domestic producers without risking a trade war is with subsidies. There are some public investments that are too expensive to miss out on just to prevent deficit spending - such as digitalization, research and development in AGI and public housing. Afterall if you don’t invest in the most recent developments, someone else will. This is exactly what we’re seeing with China and electric cars. Because of the Schuldenbremse, Germany is actively risking falling behind China in this key industry.

The problems with MMT

I see a couple of problems with MMT. I find the idea to control inflation with taxation to be pretty clever! However this leads to the first major issue with MMT - taxes can only control inflation when the inflation is caused by demand-side inflationary pressure.

What happens when the aggregate supply (LRAS - here both the classical and keynesian models) decreases? This happened worldwide in 2020/21 during the Covid-pandemic and then in and after 2022 when Russia decided to invade and imperialistically and illegally annex parts of Ukraine - in both cases the supply has decreased - there were simply less workers, supply chains were cut, production schedules were shortened (everyone remembers the PS5 shortage), less oil - which lead to higher transportation costs, which lead to everythign being more expensive. Raising taxes in this case will not decrease the inflation significantly (if at all, if society would be at full employment) and while the aggregate demand would fall in such a situation, it would not be a good time for the citizens - as everything that was expensive would get even more expensive. And don’t forget that aggregate demand is not completely elastic.

The next question on the agenda is, what exactly do we achieve with MMT if we want to increase AD with government spending, but (assuming we already have a lot of debt like in Japan) we have to issue so much currency that it might lead to noticable inflation - if we need to control inflation, we need to increase taxes, but then we paradoxically lower the aggregate demand by lowering the consumption through taxes - that way we’re back at the start with AD not increasing. The government spends more, but the government also needs to tax more, so that the aggregate demand can only improve slightly at best - this means we don’t necessarily improve the economy - in fact only an increase in the LRAS could have the positive effect MMR desires.

MMT leads to a less transparent role of the government in the economy. Large welfare states are not a bad thing, social democracies like the Nordic countries have very high tax rates and high government spendings - this way the Nordic countries have managed to humanise their economies to such a degree that life in Norway, Sweden and Finland is the best in the world. But my issue with MMT is that it wishes to enable greater government spending, but not explicitly. In Nordic countries the people know exactly how much of their money is spent by the government - it’s the tax rate, but with MMT that amount gets hidden and the transfer of value from the people to the government is less transparent. There’s also a personal component to the currency issuing question - it is a good feeling if the currency one holds has a certain value and that it belongs to you, I would much rather pay higher taxes and know eactly how much of my money goes to the government rather than the government issuing currency whenever you least expect it and the value of the currency you hold being secretly transfered to the government. High taxes (as long as the tax burden does not impact the competativeness of the companies and resources) and a budget surplus are not bad things. The Clinton administration in the US, the Cerar government in Slovenia, Germany between 2012 and 2019 and Sweden in 2005-2008 and 2022 all had budget surpluses, the Nordic countries have also had consistently high taxes - so yes it is possible to finance all government expenditures, even a social democracy, with taxes and not go into a deficit (when not in a crisis) - all it takes is a matured political culture.

On the topic of Japan - the Japanese national debt is at over 200% of the GDP. This is really not cheap, Japan needs to pay for all the interest on the debt. With MMT we would sooner or later reach the level of debt Japan has. But consequently, we would have to issue more and more currency to pay the increasing interest - but what if we need to control the resulting inflation? Taxes can only be effectively increased up to a certain degree and they only fix inflation effecitvely in the case of demand-side inflation. After a while we would be caught in a vicious cycle of ever increasing inflation and the government having to issue even more currency just to pay the interest - or risk a default.

I also just am not convinced that MMT is better than progressive taxation. If the government issues currency, then yes theoretically more funds get transferred from more affluent people (though the transfer is roughly equivalent to a flat tax). However in reality only a portion of the funds held in the currency get transferred and as we all know the wealthy do not hold most of their wealth in the form of money on a bank account but instead in the form of real financial assets, like buildings, company stock, gold etc. Less affluent people hold a much higer proportion of their personal wealth in currency and it is exactly the problem: Issuing currency only extracts value from the currency held by its users and this would affect poor people significantly more than the wealthy - it would be effectively equivalent to a hidden regressive tax. Inflation eats away the value of the money on your bank account, but it doesn’t eat away the value of a golden yacht.

Additionally MMT depends on monetary sovereignity - but if a country issues a lot of its currency, who would want to hold a currency where the government arteficially devaluates it? This is almost certainly going to lead to an Argentina, El Salvador or Venezuela situation, where the US Dollar is used increasingly by the people, because their native currencies are just not credible. The concept of monetary sovereignty weakens if the currency is used less and less by the people, thus undermining a key requirement for using MMT. This problem is bound to occur once the debt gets significantlly large enough, because so much currency will have to be issued to pay for the interest, that it will become impossible to control the inflation with taxes. This is also why, while I’m not a fan of Millei, the dollarisation of Argentina is actually a good idea.

And lastly I wish to adress a major talking point used by MMT-advocates. A lot of people argue that the public sector’s deficit is the private sector’s surplus and that is true as given by the accounting identity. But I think the conclusions that people make from the accounting identity can be misleading. So what if the government has a surplus and the private sector a small deficit? The economy is both the private sector and the government and the whole economy can be growing even if there is a private sector deficit. The private sector’s deficit pre-2001 meant that the government was simply repaying its debts - it didn’t mean that companies were worse off - on the contrary they were given their money back - money they could invest elsewhere. Private companies lending money to the government, means they have to spend less on other things - the crowding out effect - this is beneficial during recessions, but not outside of recessions. And speaking of recessions, the 2001 recession was caused by the dot-com bubble, I’m just not buying the argument that the private sector deficit was responsible for it.

Conclusion

MMT offers an alternative perspective on how governments can raise revenue. Financing the deficit through issuing currency should be theoretically equivalent to raising taxes, which offers both a basket of advantages and disadvantages.

I’m a classical Keynesian. Stimuli really do work (Obama’s stimuli lead to a much faster economic recovery in the US, compared to the austerity politics used in Italy and Greece, which have effectively wasted a huge growth potential, went through a lot of suffering and only now in 2024 see positive economic growth again) and yes having a government surplus in times of plenty is a good idea, because it slows down inflationary pressure (alternatively like in Singapore the government could mandate saving). But I’m not sure about MMT in the long run, Keynesianism has the benefit of being tried and tested - taxation, as hated as it is, remains the most transparent way to finance a government, and a government surplus is achievable.

So while I’m not jumping on the MMT-train, I think that it teaches us a valuable lesson, namely that deficit spending can be very much justified and necessary to prevent unneeded human suffering and forfeiting economic opportunities in a competitive global market.

Sources

- Stephanie Kelton, The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory

- https://www.socialeurope.eu/modern-monetary-theory-model

- https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/4/16/18251646/modern-monetary-theory-new-moment-explained